The Airport Extreme, version n, dissected.

Apple recently released their first "n-capable" base station. As usual, this base station is packaged in a beautiful case, whose form factor appears to have been chosen expressly to fit under a Apple-TV™ or Mac Mini™. Moreover, unlike previous base stations, it's design nods towards the need for cooling: The base station incorporates an intake strip around the edge at the bottom of the case, and the crease along the top is acts as an exhaust.

Under the top cover, a thick heat sink acts as a case as well as a RFI shield. The heat sink is designed to transfer the heat from all the chips at the center of the ABS to the periphery, where the passive cooling via convection through the case is supposed to happen. In my opinion, this design is marginal and I have made the decision to remove the top white plastic exterior cover, permanently exposing the heat sink directly to ambient air. I hope to lower the internal temperatures this way, extending the life of all electronic components.

After prying off the white plastic top, I also see no reason why the base station cannot be mounted vertically on a wall - the heat sink has plenty of exposure and is only warm to the touch. Plus, mounted vertically, the three antennas point in the three directions of the house that could actually contain a computer. Now I just have to find a way to mount everything on the wall... unlike the Express base station it replaced, the Extreme-n also has an external power supply, more wires, etc.

The cooling warts aside, it is a worthy successor to the previous generation of Extreme stations. Apple finally listened to the user base and incorporated more than one LAN port on an ABS. The three switched 10/100 LAN ports should suffice for most home users, even if I would have preferred a gigabit solution for future-proofing. Granted, a 100Mbit/s LAN will probably continue to be equivalent to a 300Mbit/s wireless solution, so the LAN/WAN ports are not a bottleneck for the wireless operations even at top speed... yet most, if not all, computers currently shipped by Apple have gigabit ethernet, and allowing them to talk at top speed to each other while connected to the wired network would have been a nice feature. Presumably, cost and heat nixed the gigabit ethernet switch.

Another cool new feature is the ability to attach a printer and/or a hard drive to the base station. While the previous Extreme base station could also run a printer (and most bugs related to that feature in OSX as well as the ABS firmware seem to have been ironed out), being able to attach a hard drive to create a small Network Attached Storage (NAS) drive is a nifty new feature. External hard drives with a USB 2.0 connector are inexpensive and will allow users to back up their documents, store their iTunes libraries, etc. with greater ease. Plus, a small NAS setup like this is likely to be quite energy efficient compared to leaving a computer on and having it share/serve up it's hard drive.

Once users begin to store and swap files locally, the added potential speed of a "n-capable" network will really become useful. Whereas 802.11a,b,&g networks were perfectly adequate for surfing the web, large local file transfers are pretty slow going. Here, the 802.11n technology can be seen as an enabling platform to make nightly backups less lengthy... and OSX 10.5 is rumored to have a easy-to-use backup program to make data backups easier for all users.

However, in order to realize the speed gains, you have to force your base station to only run in 802.11n mode. If it is run in "compatible" mode, it will automatically reduce its speed down to the slowest protocol that is used by a computer on the network. Thus, you could experience a drop from 300Mbit/s to 10Mbit/s (i.e. 30x) if you allow a 802.11b user to log on to your "-n but compatible-mode" network!

What makes this ABS unique though, is that you can choose among channels as well as between two frequencies (2.4GHz and 5.8GHz) to transmit on. Thus, you can continue to run one airport network for older computers on one channel (plug the old ABS into one of the LAN ports and configure it as a bridge), and make the -n network use either another channel or even another frequency. In urban environments, empty channels can be a precious commodity... the added breathing room afforded by the extra channels/frequencies is welcome.

Yet another big improvement is the new Apple Admin Utility, which acts like a installation setup wizard. Instead of confusing novice users with multiple screens/panes of settings that vary in importance, the new utility application asks users a series of questions and then sets up the ABS accordingly. Power users can still tweak away via the advanced settings, allowing for a good balance between features and usability.

Curiously, the new admin utility will only deal with the third generation of base stations and later... "Graphite" and "Snow" base stations get a separate utility. With any hope, Apple will reconsider it's stance to charge users for enabling the hardware in their already n-capable computers via a software patch. This patch is enclosed for free with with every new n-capable base station, along with the new Admin Utility. Those of us with Core Duo 2 or Xeon macs that would like to connect via 802.11n w/o buying a base station will either have to buy the software patch from Apple or pirate it on the web.

Despite the heat issues and the annoying software situation, there is a lot to like. I have not tested all the claims regarding performance (5x the speed of 802.11g, 2x the range) for this base station because I do not own an n-capable computer yet. So, I'll leave that to other sites (or testing by readers).

However, what I can offer, is an insight into the insides of the ABS, because I have never let a warranty get in the way of my curiosity. You really do not want to follow in my footsteps unless you're perfectly fine with voiding your warranty, possibly destroying your property, risking life and limb, etc. In other words, open the base station at your own peril, because (once again) Apple has not made it that easy.

Click on any picture to enlarge it

The ABS arrived, sturdily packaged... a nondescript box on the outside, as usual. |

Look familiar? |

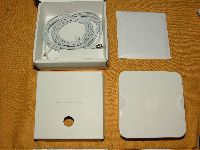

The box contents. The ABS sits on top of the other items, including the power supply (under the cardboard divider) and the driver CD's. For some beautiful and comprehensive photography of the AEBS-n exterior, look no further than the unboxing photos over at AppleInsider. |

Prying the top off with a screw-driver was the wrong way to open the ABS. If you work to disassemble the ABS from below, you may even end up with an intact plastic upper case, as shown over at iFixit.com. Their disassembly job was definitely cleaner than mine. Then again, I like my electronics to run cooler than the Jobs/Ivian design culture allow.

|

One of the three antennae on the ABS. They are found along the case edges on the three edges of the ABS that do not have any other connectors on them (front and sies, the back has all the ports). |

Here is a shot of the backside with the power port, the USB port, and the four ethernet ports (1 WAN, 3 LAN). Also note the beefy nature of the heat sink on top. All the cutouts in the heat sink are evidently there to allow convective currents to do their thing. |

Here is the outer plastic case disassembled. The edge and top cover are welded to each other, the bottom (grey) case has the rubber glued to it. Undoing the 5 screws hidden by the rubber allows you to access the metal case holding the motherboard. Don't worry, if you take off the rubber gently, you can glue it right back on. |

The underside of the assembled inner package. Note how much thinner the metal sheet stock is on this side. The metal here acts primarily as a RFI shield and less as a heat sink. A series of stamped holes in the center are supposed to direct convective air flow to the center of the base station motherboard.

|

The heat sink is beefy both inside and out. Besides the thick Al blocks screwed to the exterior metal case, they also sport heat transfer pads. Thermal management in a closed case is always going to be problematic. While Apple has a lot of experience in this field via its laptops, I would have preferred less focus on the form and more focus on cooling performance (i.e. bigger ducts to allow better passive cooling). |

Another angle. |

The motherboard. Note the mini-pci daughter-board in the top-right corner. The daughter-board is covered with heat-transfer tape. Some portions of this board are also encapsulated with metal enclosures. Note the 3V battery in a clip to the left... presumably there to keep the RAM alive? |

In the top-left corner of the Motherboard, we have two Samsung K4H651638H-3UCB DDR RAM chips (256Mbit, each). The flash memory chip from ST electronics in the top right of this picture is a model M29W128FL, which has a capacity of 128Mbit. The chip in the lower right from Marvell. I thought it could be a MV64341 MIPS system controller running the show but Kevin Purcell has shown me the error of my ways... for one, this chip does not have the right markings to be a MV64341, nor can the MV64341 actually run an AP by itself. Plus, it's too expensive. |

Further dedicated digging by Kevin uncovered that the Marvell part number most likely is 88F5181 (i.e. w/o the dash seen on the chip surface above), which would make this a standard ARM-based CPU designed to run 802.11n access points (who would have thought...). So Kevin gets two prizes: one for showing me the error of my ways, another for figuring out what the right answer is. The question is: What is the prize? |

The mini-pci daughter board. Note the three antenna wires connecting with tiny connectors to it. Heat transfer tape covers the entire board. |

Underneath the thermal transfer tape we spy a AR5416-AC1E Atheros chip, which seems to be part of a standard Atheros (the AR5008-3NX platform). If you look closely at the lower logic board pictured on the second page of the Atheros bulletin, this board will look very familiar (look for it in the upper right corner of the AP board). |

Underneath that metal enclosure we spy another Atheros chip (model # AR5133-AL1E), and 3 smaller chips (one for each antenna) with "WN6M3, FM1011" markings on them that take care of the RX/TX at 2.4 as well as 5.8Ghz. On the right edge, you can see the three Hirose mini coax jacks that the antennas plug into. You can read more about the Atheros XSpan reference platform here. (Thanks Kevin) |

The underside has a sticker to designate the MAC address and serial number for this daughter-board. I have removed the S/N and MAC ID numbers for privacy reasons. |

Here is the hole in the motherboard that is left when the daughter-board is removed. Note the ventilation cut-out below. |

In this shot you can see some of the chips I have mentioned earlier, along with the antenna on the front edge of the unit, along with the little white shield that surrounds the status LEDs. Barely visible in the back right is the 3V battery. |

Another top-side shot of the motherboard, detailing the Ethernet, USB, and power ports. |

Inside that enclosure hides a Broadcom chip, model BCM5325E1QMG, which can act as a switch for up to six 10/100 ports. Presumably, a gigabit switch would have been too expensive and too hot for this enclosure. |

Here is the underside of the motherboard. |

Yet another precision stamping covers a portion of the motherboard on this side. The cutout to the left is the ventilation shaft for the daughter-board. |

Underneath the cover, more chips. The biggest one is from Texas Instruments, model 66E71YK, A1VCM162260. |

A better angle on the Ti chip. Beautiful stamping, BTW. |

Here is a cross-section of the ABS with the base back on. Evidently, air is supposed to be drawn in via the bottom slit / plenum and then released with the slit near the top of the white plastics. |

A close up. Note the status indicator LEDs mounted on the motherboard to the right-hand edge of the board. To the left of the LED's is one of the antennas. The flash on the camera is strong enough to show you the circuit traces. |

The backside, showing all ports, and the reset button (at far right). |

The reset button in detail. |

Postscript:

There is a lot to like about the new base station, with the neatest feature being the hard drive capability. Network-Attached-Storage (NAS) has the potential to allow most users painless backup strategies, serve up iTunes for the whole family, etc. without using as much power as the average home computer. That said, the wireless speed potentials claimed by Apple have yet to be reached in real-life conditions and any backups via ethernet or wireless are going to be far slower than attaching a drive directly to a computer. So, while interesting, this is a entry-level NAS solution, and backups should be run overnight. Allegedly, OSX 10.5 will make that part easy.

For industrial-strength NAS-systems, I'd look at something like the Infrant NV, since this system has RAID 5/XL capability (for better data preservation), faster throughput (it has a gigabit ethernet LAN port), support for jumbo frames, AFP 3.1, etc. In other words, for a couple hundred bucks more, you get a file server that can walk and chew gum at the same time, that can act as a iTunes or Slim file server right out of the box, etc. But even with gigabit ethernet connections, you only get 5-20MB/s file transfer speeds, a far cry from what hard drives or RAID systems can do when attached directly to your computer.

But as a entry-level router, file server, and print server, the Extreme-n does quite nicely. The new airport admin 5.0 software (though still buggy) is much easier for novice users to understand than its predecessor. This ease of use is the primary reason to shell out some extra dough for the Apple solution over the many 802.11n alternatives out there that sell for less.

What bugs me the most about the Airport base stations is the continued issue of heat management. None of them are great at it, and the Extreme-n, while a bit better, is still a far cry from perfect. Given how hot it runs, I fear that there will be another rash of Airport base station failures in the future. Thus, I will leave the lid off mine, and another project in the works is retrofitting cooling to the Express' base stations I have, since high heat seems to make them flaky performers also.